The preliminary results were quite humorous:

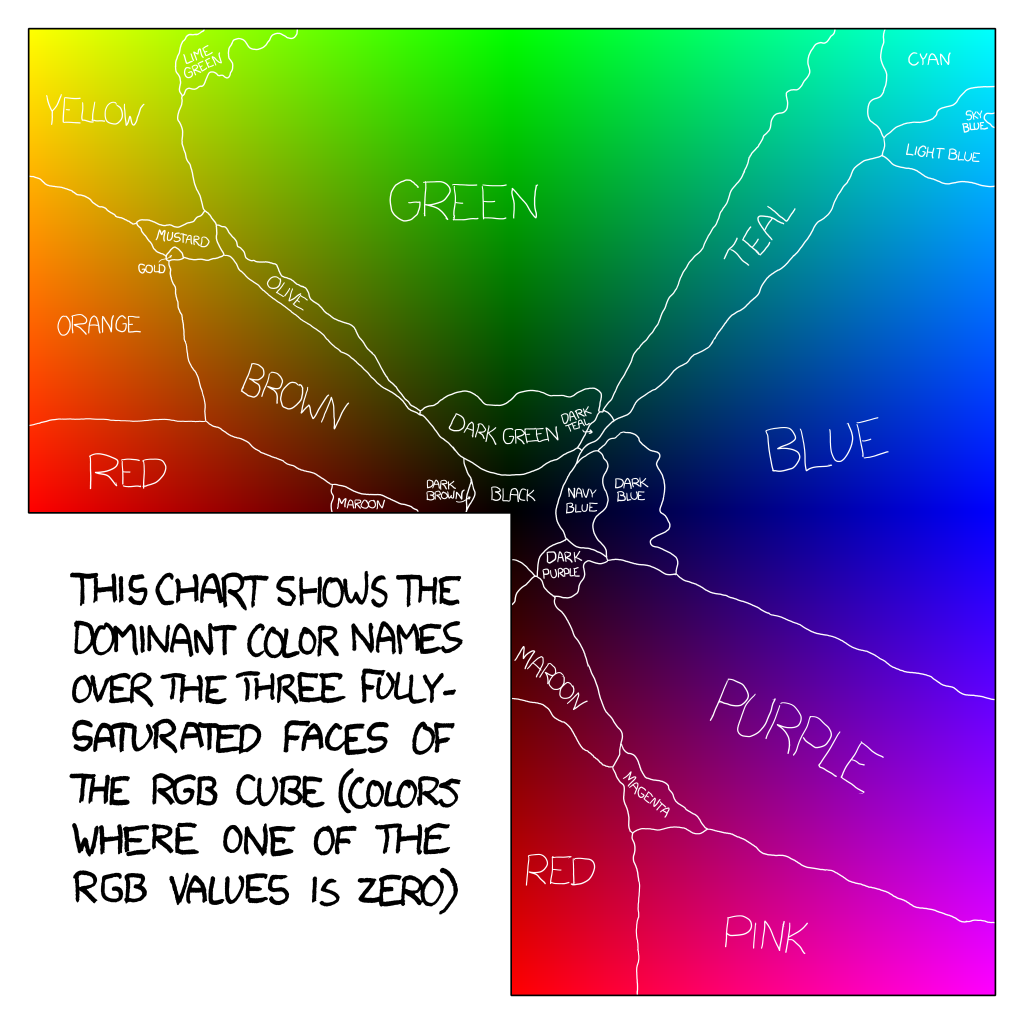

A color spectrum was also divided into the various "accepted" realms of color:

- If you ask people to name colors long enough, they go totally crazy.

- “Puke” and “vomit” are totally real colors.

- Colorblind people are more likely than non-colorblind people to type “fuck this” (or some variant) and quit in frustration.

- Indigo was totally just added to the rainbow so it would have 7 colors and make that “ROY G. BIV” acronym work, just like you always suspected. It should really be ROY GBP, with maybe a C or T thrown in there between G and B depending on how the spectrum was converted to RGB.

- A couple dozen people embedded SQL ‘drop table’ statements in the color names. Nice try, kids.

- Nobody can spell “fuchsia”.

All very interesting, but if we think about it, this is a definition of colors of the English speaking world (primarily - most likely - that of the United States). In a more discursive review, EmpericalZeal writes about how color is defined differently in different languages:

Blue and green are similar in hue. They sit next to each other in a rainbow, which means that, to our eyes, light can blend smoothly from blue to green or vice-versa, without going past any other color in between. Before the modern period, Japanese had just one word, Ao, for both blue and green. The wall that divides these colors hadn’t been erected as yet. As the language evolved, in the Heian period around the year 1000, something interesting happened. A new word popped into being – midori – and it described a sort of greenish end of blue. Midori was a shade of ao, it wasn’t really a new color in its own right.EmpericalZeal continues, describing the xkcd color spectrum, and raising the question of what this all means for the non-English-speaking world, drawing upon the World Color Survey that sought to determine how many colors exist (linguistically), and found that there seemed to be pattern in the development of different colors:

In modern Japanese, midori is the word for green, as distinct from blue. This divorce of blue and green was not without its scars. ... [In] Japanese, vegetables are ao-mono, literally blue things. Green apples? They’re blue too. As are the first leaves of spring, if you go by their Japanese name. ... In Japanese, [someone who is inexperienced is] ao-kusai, literally they ‘smell of blue’. It’s as if the borders that separate colors follow a slightly different route in Japan.

And it’s not just Japanese. There are plenty of other languages that blur the lines between what we call blue and green. Many languages don’t distinguish between the two colors at all. ... The Korean word purueda could refer to either blue or green, and ... this is something you see across language families. In fact, Radiolab had a fascinating recent episode on color where they talked about how there was no blue in the original Hebrew Bible, nor in all of Homer’s Illiad or Odyssey!

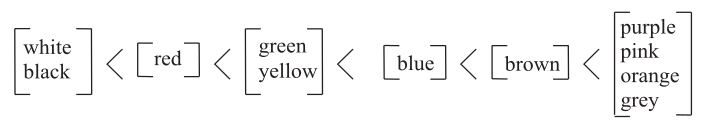

A picture worth many words. The path to a more colorful language, according to Berlin and Kay (1969).

Pretty cool, eh? But so what? Well, in part 2, EmpericalZeal explains why:... If a language has just two color terms, they will be a light and a dark shade – blacks and whites. Add a third color, and it’s going to be red. Add another, and it will be either green or yellow – you need five colors to have both. And when you get to six colors, the green splits into two, and you now have a blue. What we’re seeing here is a deeply trodden road that most languages seem to follow, towards greater visual discernment (92 of their 98 languages seemed to follow this basic route).

Well, if we agree with the idea that our perceptions of the world have a major influence on how we think about the world, and we further agree that our how we form our perceptions are limited and enhanced by the traits of our language, then we have to recognize that language plays a major, foundational role, in how we even put together our thoughts about the world in which we live. This is the basic point of people following the thesis of the American linguist Benjamin Whorf, who said:

We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way—an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language [...] all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similarAnd we know this sort of thing to be true (and it is the basis of my reasoning in this blog post), and that terms that we might individually think of as fixed and true may only be so in our minds (such as what is meant by the term "environment" or what you mean by "brook"). It's a major part of political strategy (including the whole "climate change" vs. "global warming" semantic debate, "War on Drugs" and "Drug Tzar" framing, the semantic arguments that underlay "climate gate", the misunderstanding of scientific word-use, etc.), and as words change their popular imbedded meanings, their social use also changes (e.g., "welfare" vs. "the dole"). Indeed, going back to the linguistic connections with available words for colors, EmpericalZeal describes the results of a 1984 color recognition study amongst English and Tarahumara speakers:

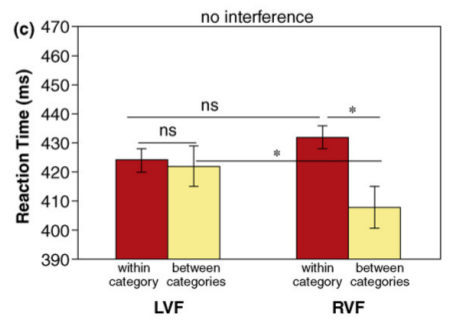

The researchers discovered that, compared to the Tarahumara, English speakers do indeed see blue and green as more distinct. Having a word for blue seems to make the color ‘pop’ a little more in our minds. But it was a fragile effect, and any verbal distraction would make it disappear. The implication is that language may affect how we see the world. Somehow, the linguistic distinction between blue and green may heighten the perceived difference between them.Pretty cool, eh? EmpericalZeal then describes a 2006 follow up study that was a color perception task in which a peripherally viewed block of color would be a contrasting (bluish or greenish) color compared to the other peripherally viewed blocks of color. What the researchers found was:

It takes less time to identify the odd colored square if you are jumping categories (blue versus green), compared to staying with a category (green versus green). ... However, ... this result only holds if the differently colored square was in the right half of the circle. If it was in the left half, then there’s no difference between the two cases – blue and green are just as vivid. It seems that color categories only matter in the right half of your visual field!

WOAH! So color perception and recognition have handedness too? Perhaps so! I wish that this study were done by obligate lefties (i.e., lefties who can't actually learn to do things with their right hands). Would we get a different response?

Still, this finding extends beyond English speakers to include Koreans' distinction between yeondu and chorok versus a lack of real distinction between the two (as distinct colors, as opposed to shades of greeny-yellow) in English. The results showed that Koreans displayed the above type of distribution (i.e., no significant difference when viewed in the left half of the circle; significant difference when viewed in the right half of the circle), while among English speakers, there was no significant difference when viewed at either the right or left side of the circle... which seems to reinforce the idea that, since English doesn't distinguish these as distinct colors while Korean does, having a basic color distinction (as opposed to shades of the same color category) does change how you observe the same physical phenomenon.

EmpericalZeal continues in describing how different cultures describe color relationships differently, using the following BBC video as an example:

as well as how it takes children a significantly longer amount of time to learn to distinguish colors as opposed to acquiring words for objects, showing that Darwin's inquiry of whether children perceive the world differently once they learn their colors is very likely true.

I've covered (and blockquoted) a LOT of EmpericalZeal's blog posts, but I really am excited about a lot of what was written there. Still, you should go over to those two posts in order to read them in their entirety:

The Crayola-fication of the world: How we gave colors names, and it messed with our brains:

No comments:

Post a Comment